Projects

Sound and Fury

Sound and Fury

Having staged Hamlet inside Grand Theft Auto during lockdown in 2022, Pinny Grylls and Sam Crane set out to fulfil their dream of bringing Shakespeare back to the stage — while simultaneously performing inside a computer game.

Sound and Fury explored how live performers and digital avatars could share the same dramatic space, with audiences able to participate either remotely or in person. Layers of projection, sound, and responsive design transformed each performance into something unpredictable, immersive, and inclusive.

We asked: can a real actor and a digital avatar share a meaningful dialogue? What does “liveness” mean when physical and virtual realities overlap? And what new forms of drama emerge when audiences stop being spectators and become active “players” shaping what unfolds?

The EXPERIMENT grant allowed us to begin developing Be The Players Ready which then evolved into Sound and Fury — a new hybrid performance that explores what happens when Shakespeare collides with gaming.

Experiment

£20,000

Aims of the Project

Our goal was to create a bold, immersive reimagining of Shakespeare — one that merges live, in-person performance with the dynamic, unpredictable energy of gaming worlds.

We wanted to explore what “liveness” means when actors and avatars share the same stage, when code and flesh perform side by side, and when audiences are no longer just spectators but active players shaping the story. At its core, the project examines questions of control, fate, and free will — themes that bridge the worlds of theatre and gaming.

We set out to push the boundaries of what hybrid immersive theatre can be — testing how digital performance, responsive environments, and audience interaction could create genuine dramatic agency and emotional depth.

As a Deaf artist, Pinny was also determined to make accessibility an integral part of the art form itself. Captioning, BSL, and haptic design weren’t to be “add-ons” but expressive tools — woven into the visual and sensory fabric of the show, expanding how everyone could experience and feel the story.

How did they do that?

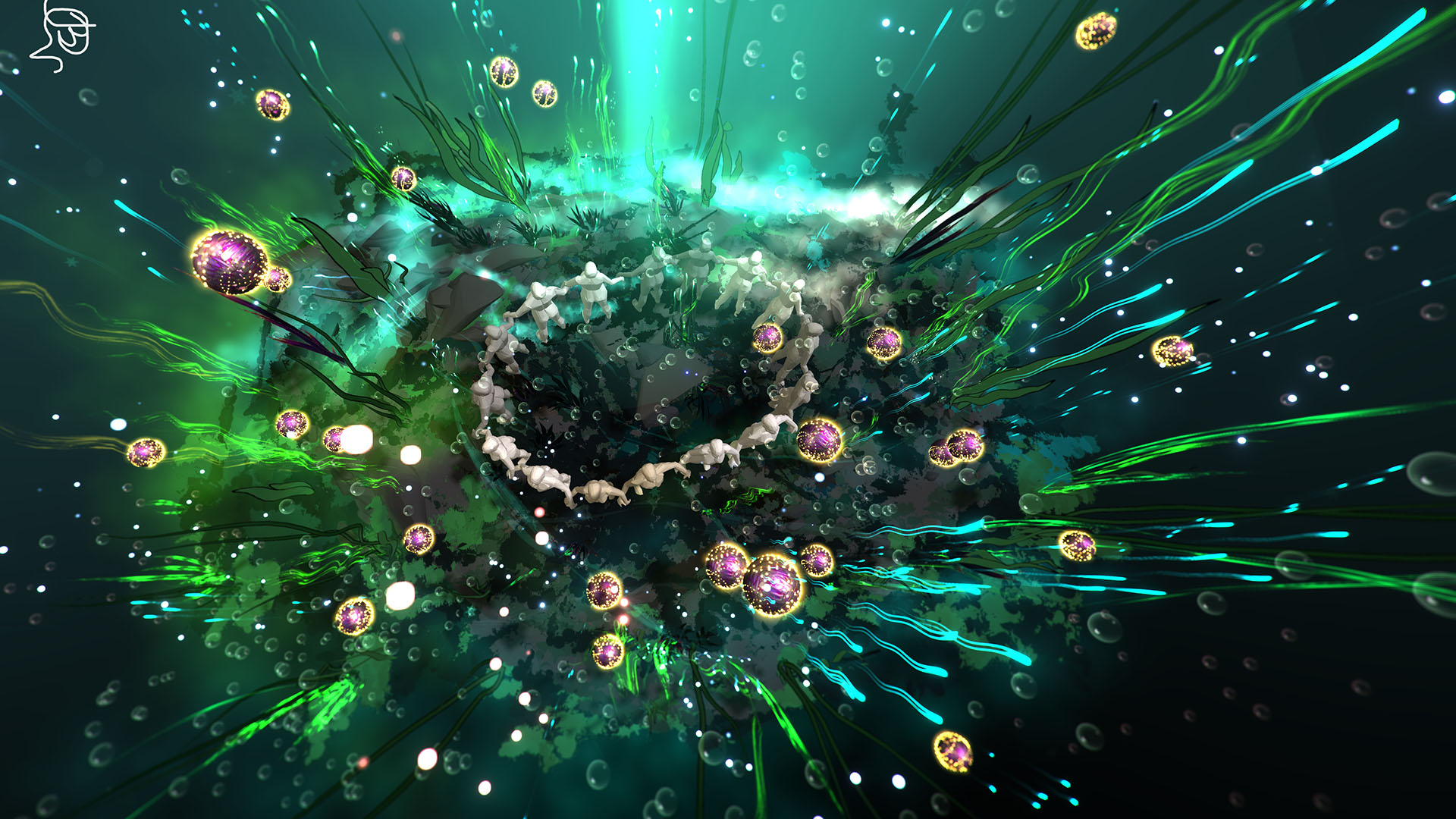

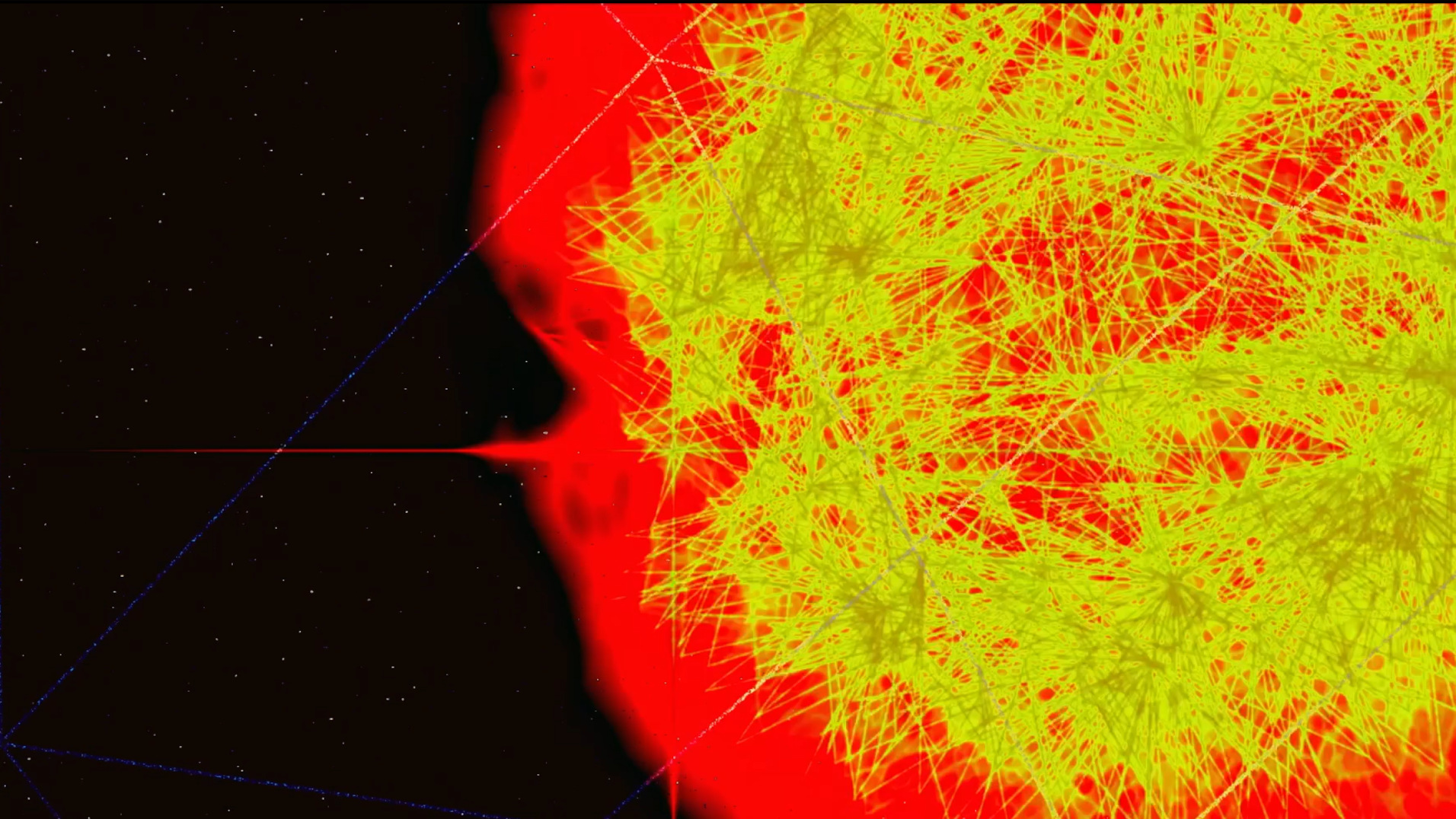

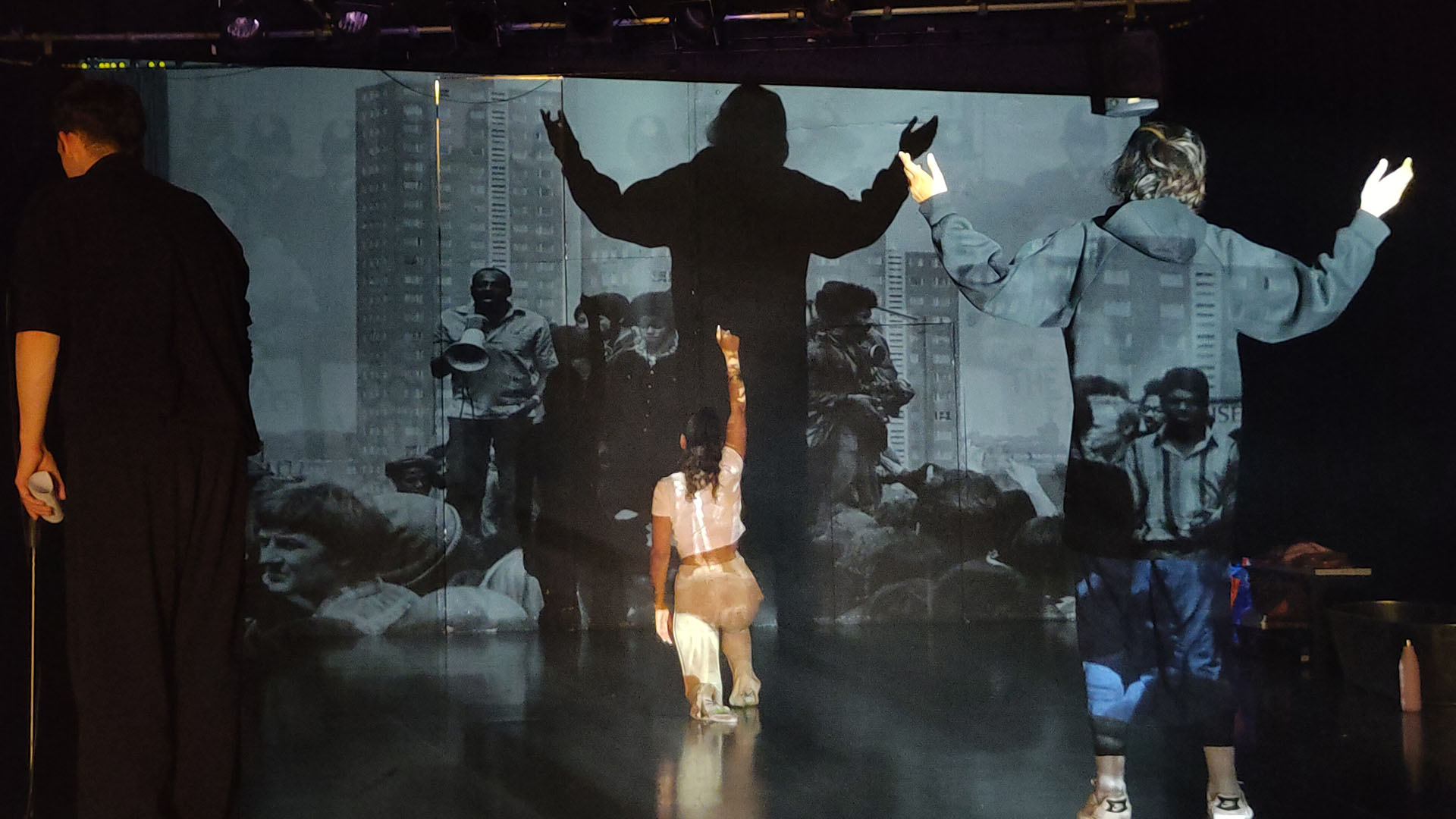

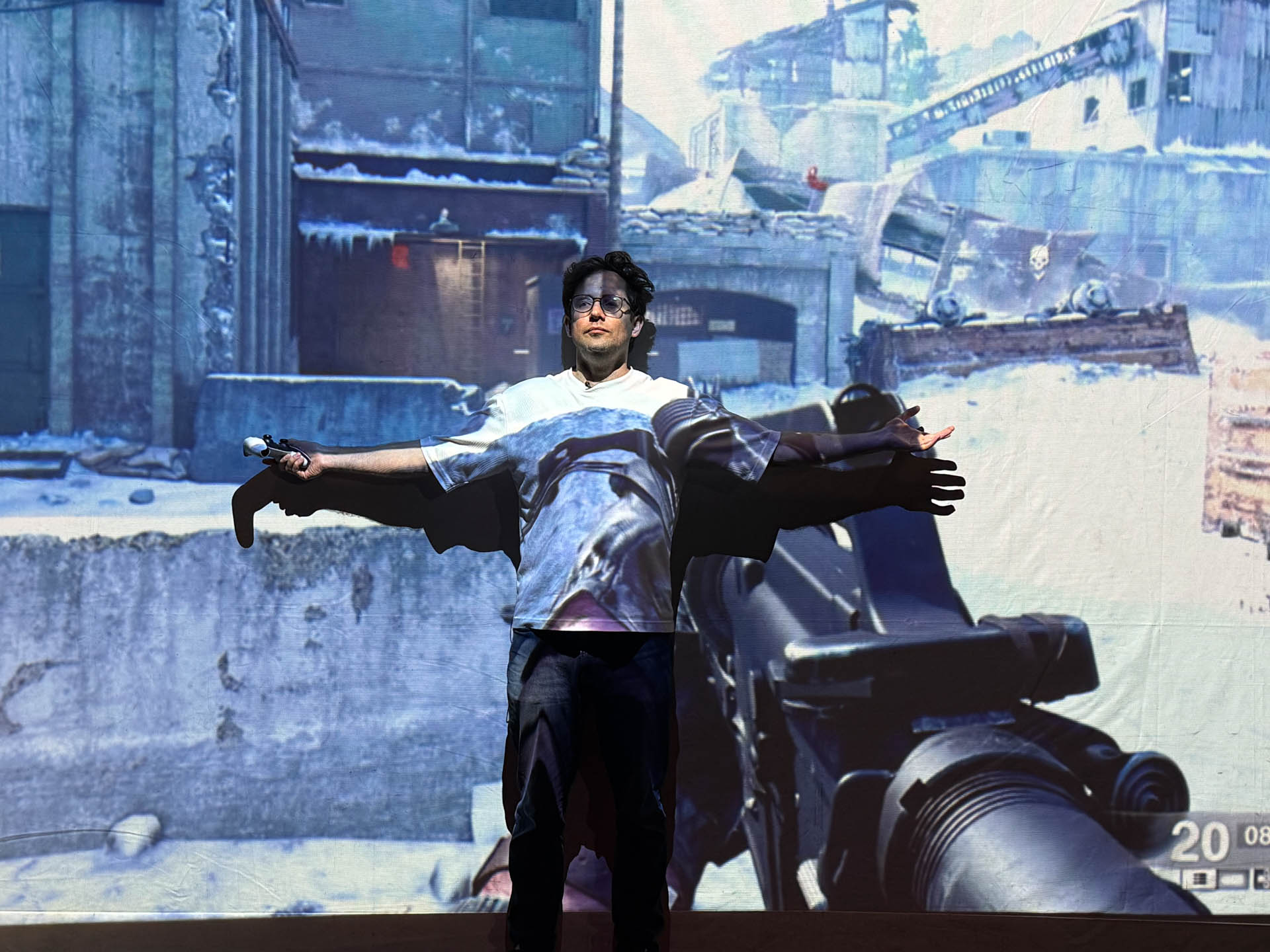

We began by testing how digital and physical worlds could truly share a stage. Early experiments showed us that we preferred multi-screen projection to LED screens — running five PlayStations simultaneously with multiple gameplay feeds projected behind live performers.

The result was haunting: actors moving in shadow beside their glowing digital doubles, their gestures echoed, fractured, and reformed in real time. Working with a movement director, we found that this interplay between live and virtual bodies created moments of unexpected intimacy and emotion.

Actor–avatar interplay became the heart of the piece. We explored deliberate dissonance — when the avatar resisted its human controller sometimes even turning to murder the real actor on stage— and found that connection and conflict between the two redefined what “puppetry” could mean in a digital world.

For audience participation, we first tried giving individuals direct control of avatars, but this felt chaotic and shallow. The breakthrough came with collective “flashmob” actions on Discord — audiences joining forces online and, in the theatre, to form battle scenes. Suddenly, participation became storytelling: tense, communal, and electric.

Our sensory design extended this hybridity into the body. Responsive lighting pulsed in sync with game pixels; haptic vests transformed sound into vibration, letting audiences feel the battle rage.

Finally, we embedded accessibility as art. Creative captions became living visuals, BSL interpreters moved within the scene as spectral presences or through Discord servers, and these layers didn’t just include Deaf and disabled audiences — they deepened the atmosphere for everyone.

Each experiment taught us that technology isn’t the spectacle — emotion is. The tech just lets us reach it in new ways.

Some of the most powerful moments came from messing around and experimenting playfully – and even from unexpected glitches in the tech — when live and digital worlds didn’t align, but clashed.

Challenges and discoveries

Remote participants initially felt disconnected, but projecting them into the performance space gave them visibility and presence, uniting both live and online audiences.

A key breakthrough was realising that group audience action in the form of ‘Flashmobs’ co-ordinated through Discord – was so much fun! Collective participation rather than individual control — created the richest dramatic results.

Moments of glitch or technical imperfection often turned out to be creatively useful, introducing unexpected textures of liveness.

Tips for other artists

Don’t smooth everything out.

Sometimes it’s the rough edges between digital and live that carry the strongest emotion.

Inclusion as Creative Practice

Accessibility was embedded at the heart of the experiment.

Working with Deaf artists and creative captioners, we discovered that captioning, BSL, and sensory design are not just tools for inclusion — they can expand the artistic vocabulary of performance itself.

The programme gave us the freedom to experiment with the hunch we have had all along – that immersive theatre and gaming have more in common than people think. The R&D support enabled us to test a radical new performance language that felt truly accessible and exciting to participating audiences.